Written by Hayley Scanlon on 13 Dec 2011

Distributor N/A • Certificate N/A • Price N/A

Yoshihiro Tatsumi might not be as well known, in the West at least, as some of his contemporaries but his work has certainly been hugely influential to today’s manga artists. Fascinated by manga as a small boy in post-war Japan, the young Tatsumi began by drawing comic four panel manga strips and entering them in various competitions for prize money. Although he was often successful, he found himself growing bored of the four panel format and became more interested in long works. Eventually a series of fortunate events allowed him to meet his great hero Osamu Tezuka, who became something of a mentor to the young artist.

However, as he grew older and experienced the ups and downs of the manga business, he became increasingly frustrated by the rigidity of the manga form. He began wanting to make an anti-manga, a manga that wasn’t a manga at all. Tatsumi wanted the freedom to be able to deal with adult topics, characters with real psychological depth, and sophisticated plotting. The name he came up with for this new kind of mature manga was ‘gekiga’ (dramatic pictures), and it was under this banner that Tatsumi was to do his most important work.

Eric Khoo, the director of this film and a former illustrator himself, is a long-time fan of Tatsumi’s work and wanted to make this film as a sort of tribute with the hope of bringing this work to a wider audience. Based largely on Tatsumi’s 2009 autobiographical manga A Drifting Life, the film tells the story of Tatsumi’s career from drawing comic manga for prize money to becoming one of Japan’s foremost manga talents - winning the Japan Mangaka association award in 1972 and coming full circle with the Osamu Tezuka cultural award for A Drifting Life (alongside a fair few Eisners to boot).

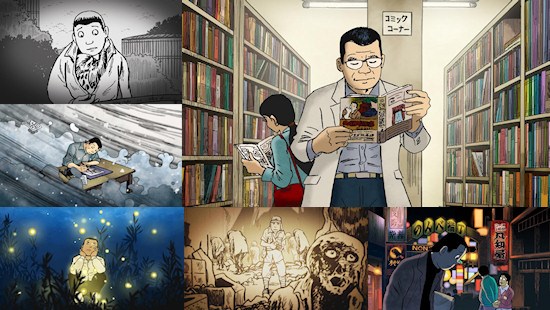

The film begins with the epilogue from the book - Tatsumi leaving the seventh year memorial service for Tezuka and recalling all his fond memories of working in the industry over the years. The autobiographical sections are narrated by Tatsumi himself and illustrated in full colour with a beautiful colour palette reminiscent of colour manga. Alongside his own biographical details, as he did in the book, Tatsumi sets the scene a little by adding in contemporary events from Japan such as popular songs or political developments. Cinema in particular was a big influence on Tatsumi’s work, both Japanese and international, so of course there are a lot of references to film.

Slotting into the biographical narrative, Khoo has animated five of Tatsumi’s short stories. These are mostly monochromatic until the final instalment which is in muted full colour. The first of these, Hell, is set in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing as a young soldier is sent to the scene to gather evidence and provide assistance. He takes a photo of the shadows of two people burnt onto a wall and comes to the conclusion that the scene depicts a son massaging his mother’s shoulders. Years later the photo becomes a sensation as a portrait of desecrated innocence speaking out for the victims of the disaster and turns its owner into a speaker for the victims’ movement. However, all may not be as it seems and there might be grim consequents for all concerned.

In Beloved Monkey a factory worker dreams of a better life and finally decides to hand in his resignation only to end up losing his arm in a workplace accident. Losing his job and finding himself unable to get another one because of his disability, he becomes increasingly isolated and withdrawn. He even fails to connect with his pet monkey who mostly sits silently with his back turned to his owner, staring at the wall. Eventually the factory worker comes to a decision he thinks is for the best, but he can’t know how wrong it’ll turn out to be.

Moving on in time slightly, Just a Man is the story of an embittered salary man who’s approaching retirement age but loathes his wife and daughter so much he can’t bear the thought of it. He decides to squander all his savings so they can’t have them and decides to do so by having a real love affair to get back at his wife even more. However as you might have guessed things don’t go as well as he’d hoped.

Good-Bye is perhaps the harshest and most extreme of the stories. Illustrated in a deep sepia tone it tells the story of a prostitute who is saying goodbye to her GI lover. Interrupting this scene, the woman’s father turns up and refuses to leave even though he’s made very unwelcome. The woman obviously blames her father for her present fate and in a drunken attempt to get rid of him forever she seduces him.

The final tale, Occupied, is a much more whimsical affair where a frustrated children’s illustrator becomes obsessed with the pornographic graffiti in a public toilet. This is much more obviously set in the ‘70s and everything is appropriately drab looking, full colour but slightly muted.

Some might criticise the animation style as lazy, which I wouldn’t agree with, but it is highly stylised. Attempting to stay as close as possible to Tatsumi’s manga designs, the animation is more of a cut out style with quite stiff motion and a lot of stillness. There is a worrying section around the title sequence where it feels a bit ‘motion comic’ but thankfully this doesn’t last too long. The only other problem is that sometimes there is mouth movement accompanying the voice over, and sometimes there isn’t. It isn’t a big problem I suppose but it is a little odd and more consistency might have been better. Most impressive and moving is the scene near the end where the animated Tatsumi suddenly dissolves into the real one, still drawing away.

For those who have no interest in manga or its history, Tatsumi might not have very much to offer but for those who do it is a beautifully rendered tribute to a great figure of the art form. However, the film does feel slightly torn between its biographical and dramatising aspects. Perhaps the five shorts might have been better seen separately and more of the film given over to Tatsumi’s own story. The film does feel episodic - constantly breaking away from the main narrative and then back again so often without any kind of explanation or context into which to put the short stories. It doesn’t quite feel coherent as a whole somehow and might have worked better if it were more tightly integrated. Nevertheless, this is beautiful and engaging film which will please existing fans of Tatsumi’s work whilst being perfectly accessible to the uninitiated.

Tatsumi was screened as part of the One Dot Zero festival hosted at the BFI in London

by Ross Locksley on 08 Feb 2026

by Ross Locksley on 25 Jan 2026

by Ross Locksley on 01 Jan 2026

by Ross Locksley on 21 Dec 2025

by Ross Locksley on 25 Nov 2025

by Ross Locksley on 24 Nov 2025

by Ross Locksley on 11 Nov 2025

by Ross Locksley on 08 Nov 2025