Written by Jared T. Hooper on 17 Feb 2026

Distributor VisualArts • Price £6.99

Visual novels are a medium I've always wanted to get into but couldn't quite manage. I've read a few—Katawa Shoujo, If My Heart Had Wings, A Sky Full of Stars—as well as several of their adventure game cousins—Ace Attorney, AI: The Somnium Files—but it's a habit that never quite stuck. It's an especially bad habit to not have this habit but still pile on the visual novels in my Steam backlog under the vague promise that I'll get to them someday. So, unrelated to the turn of the year, I resolved myself to break into the habit of reading more visual novels, and to start things on easy footing, I opted for a title 4-5 hours in length, that being Planetarian ~the reverie of a little planet~ by the famous Key.

Why don't you come to the planetarium?

We begin with a panning view of a Japanese street as an unknown woman's voice invites us to a planetarium, where we can behold the beauty of the stars. We seem to then enter that planetarium, but while the setting is the same, the time period isn't.

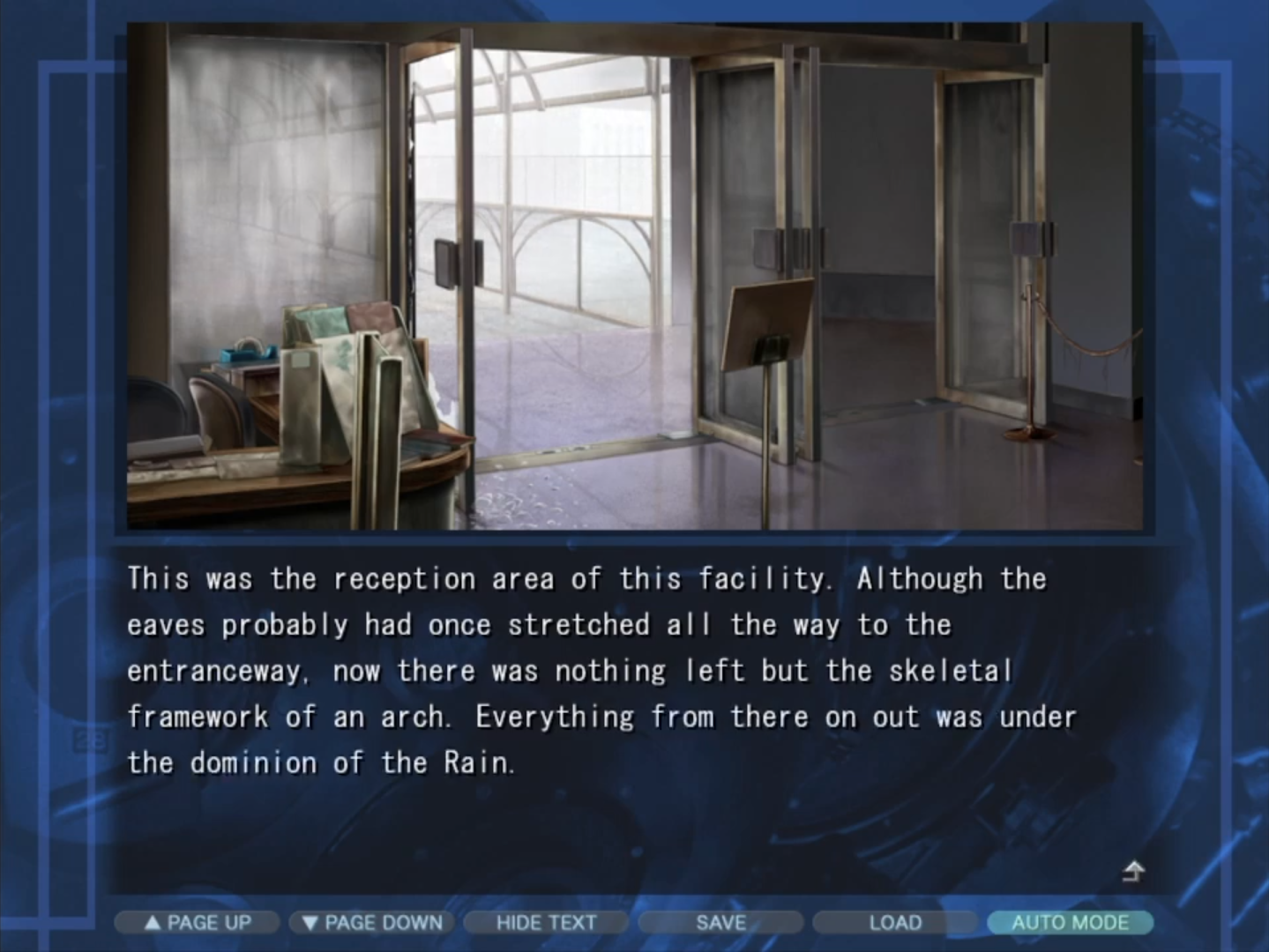

Planetarium takes place several decades in the future, after endless war and strife has wiped out most of humanity, with only a few scattered settlements left behind and tucked away from the many dangers plaguing the land: leftover munitions, autonomous war mechs, an unending acidic rain, even other humans. The perspective belongs to one such human, known only for his title of Junker, a type of post-apocalyptic scavenger, as he infiltrates a domed facility, believing it to be a military installation or weapon of some kind, only to find out it's a planetarium staffed by a lone, dedicated, friendly, quirky, and rather chatty robot, Hoshino Yumemi. Having known nothing but the wasteland and survival by scraping by, Junker is confused by her early-century gestures and put off by the seeming meaninglessness of them. But, losing a stubbornness contest to a robot that won't take no for an answer, he sticks around, helping fix the broken projector necessary for the planetarium show she urges him to bear witness to.

The beautiful twinkling of eternity that will never fade, no matter what.

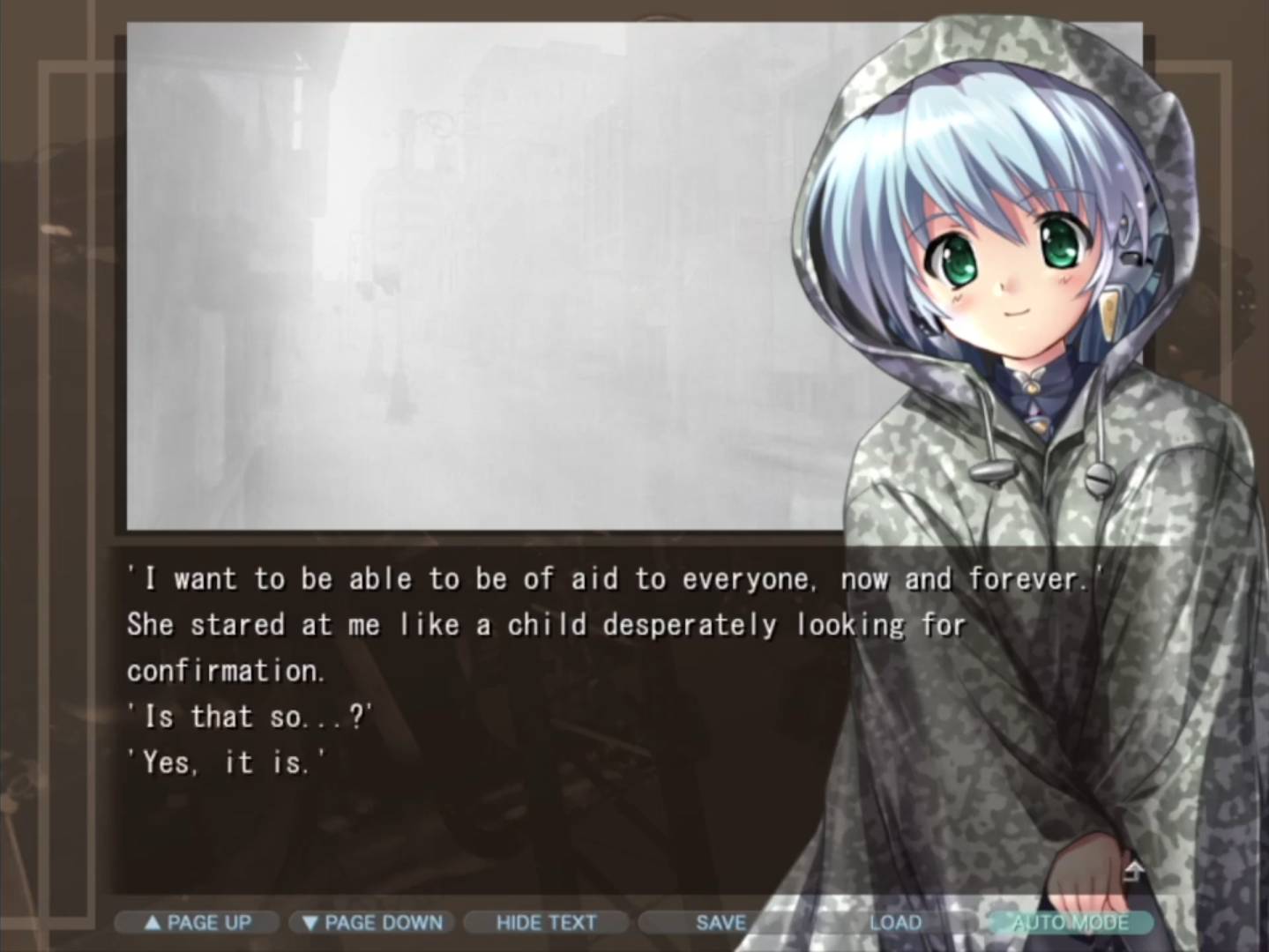

Before getting into the weeds of the story, I want to note that what I played was the original release of Planetarian before it was delisted from Steam in 2022 and replaced with the HD version. (Yes, Planetarian's been comatose in my backlog for that long.) Going back and forth between comparative screenshots, backgrounds are largely unchanged, with maybe some additional glints of light on certain objects, but Yumemi's artwork has been completely redone. Her linework and shading are much crisper in the HD version, and her color palette's more monochrome. In the SD version, her shoulder pads are a dull gold that contrasts against her pale blue hair, whereas her hair's tone shifts closer to purple, as do her shoulder pads, in the HD release. The difference in lighting is what I find most striking. In the SD version, Yumemi's whole person is cast in this gold as though she's standing in a sunset, and her HD artwork is more plein-air, with flatter lighting that isn't so pronounced. Both editions look great, though my preference is for SD Yumemi, probably because she's who I spent four hours with, but also because, like many others in my generation, I've taken up a recent fascination with retro and classic objects and aesthetics, and that includes 90s and 2000s anime. If there's one thing I do like better on HD Yumemi, it's her ribbon. The addition of lighting gives it proper shape as a three-dimensional object, whereas her SD ribbon struggles to look more than 2D. Curiously, the bouquet she's holding in the HD version looks to be the exact one from the SD version, just sharpened.

The standard layout for a visual novel is the background filling up the whole screen, cowboy shots of characters pasted on top, and textbox overlain them at the bottom. Planetarian shakes up this layout by shrinking the background so that it floats over a second backdrop of JENA, the planetarium's projector, with Yumemi standing over both backgrounds but still behind the textbox, which has much more real estate than what other visual novels allot. This framing gives Planetarian an almost storybook feel, as though Yumemi isn't just a character in this story, but a sisterly or motherly figure sharing it with us. Majorly different as these two games are, it reminds me of the intro sequence to Yoshi's Island, which shows its visuals in a narrow strip, with text scrolling beneath on the black background. In some strange way, Planetarian does feel like a bedtime story. Not one for children going to bed, but an elderly person lying on their deathbed, ready to cross over at any moment, so they're told this story of the stars and the human desire to touch one.

All the stars in the sky are waiting for you.

The prose in Planetarian is excellent. It possesses a literary style whose lush descriptions served to immerse me into the setting just as much as its washed-out backgrounds or the static-like animation of the driving rain. Even the pauses in paragraphs, before another line is added, add a certain weight to the pacing and demand focus on what appears as it appears, not as an upfront whole. Planetarian has a talent for using every tool available to its medium to tell its tale. Cheery music when speaking with Yumemi lightens the mood, or the lack of music, paired with the ambiance of rain, will make for sobering, thoughtful scenes. My favorite track in the story is The Robot and the Rain, this contrasting combination of profound pads and an optimistic, if childish, recorder, which encapsulates what this story is: a deep examination of hopeless circumstances with baseless optimism for a guide.

As much as the music, the story's sparse sound effects are put to tremendous use, from the steady, melancholic droning of the rain to the loud, startling cracks of gunfire. Planetarian isn't a horror story however stretched, yet its climax is punctuated with this layered cacophony of banging metal and grinding steel that's as disturbing and unsettling as anything haunting a PSX horror title.

My favorite usage of its tools is how it handles its visuals. Halfway through the story, Junker and Yumemi are in total darkness, rendered by deleting both backgrounds, painting the screen totally black, and in comes Yumemi, using her ribbon as a flashlight to illuminate what darkness she can. It feels exactly like times when my power's gone out at night, so everybody in the house gathers together in the living room, using flashlights or candles to see. It's a surprisingly and unintentionally intimate scene in the story, and what follows is a total abandonment of visuals, asking you, the reader, to envision what the narration describes, and to put back into place the visuals to this visual novel. It's nothing too different from what the remainder of the story demands, using prose to fill in actions and scenery, but under the context of this scene, it works exceptionally well. There is a slight damper when it reintroduces images when there aren't supposed to be any, but it manages to work even that so splendidly well that I can forgive it. Truly, I could dissect every little thing about this particular scene and gush at length about why it's so beautiful, mesmerizing, impactful, and whatever other synonyms for great you'd wanna pluck out a thesaurus, but what my words can't accomplish that this scene does is instill the emotions of wonder and awe, and really, it's best experienced firsthand for yourself and not by reading the random yammering of some uninteresting fellow online. Actually, that applies to the story as a whole, but I digress.

For those who do plan on experiencing Planetarian for yourselves, I do have to note that it's not the most exciting of stories. More than 90% of it consists of conversations between Junker and Yumemi and the former occasionally stepping away to repair the broken projector, with the only breaks being flashbacks to explain how the world came to be in the state it's in, but then once it's given all the exposition it needs, all attention is squarely on our only two cast members and the push and pull of their views of this world and beyond it.

Junker is a cynical and practical man, only out for himself, having even battled three other junkers for scavenging rights to the city before the story's proper start. Yumemi, meanwhile, is a positive, happy-go-lucky, and slightly malfunctioning robot built for the express service of shuffling customers into the planetarium and guaranteeing a wonderful visit. They're at complete odds, their meeting the rubbing of a brick and a cinder block together as either tries and fails to sway the other to their standing. From the outset, Junker, cold and abrasive as he is to Yumemi's hospitality, because of the world's situation, has the easier position to sympathize with. He finds Yumemi incredibly annoying, and true be told, I did so, too, to a small degree. He hates her incessant chatter, where I found it frustrating how Junker could instruct her to please be quiet, please, and her response was always, “I'm so sorry for talking! I'll stop talking immediately! By the way, would you like a coupon to the flower shop on the first floor of this department store?”

At the same time, I understand where Yumemi's coming from. She's a robot who, sophisticated as she is, has limited programmed priorities, and responses to anything not within her purview simply don't exist, which results in a lot of repeated lines, a trait I find irritable in human characters where their one or two catchphrases become their defining characteristic, but for Yumemi, I understood her and sympathized. It was sad watching her stand out in the rain, practicing her common invitation should any customers show. Junker knows they won't. I knew they wouldn't. Yet Yumemi, despite what she sees, still believes, by her own flawed logic, that customers will someday return. It's the same brand of unwarranted optimism the fresh-out-of-high-school me carried proudly on his sleeve, that I wish the chip-on-his-shoulder me of today could once more grab.

In the most nihilistic setting imaginable, Planetarian asks one simple question: What purpose is there in enjoying something meaningless? Junker isn't wrong. When the world's nothing but ruin and decay, concerning oneself with faraway giant balls of gas won't fill a stomach. The only place he finds something resembling joy is at the bottom of a beer bottle, and even that can be a risk to his life. Before the story's beginning, his mentor lost his life after falling for an “obvious trap,” and Junker, in one scene, hand outstretched for a lonesome beer bottle, recalls his mentor's last moments and hesitates. It's Yumemi who grabs the beer bottle and hands it to him. Given the circumstances, it's a reckless act on her part. But dig down and her behavior here is one small service for the great act she does for Junker.

Ask Yumemi that one simple question and she would tilt her head curiously and remark with a great smile on her lips, “Because they're beautiful.” She needs no reason, no excuse. Very much like a child, for whom being alive to experience that beauty is enough for them, as it should be for all of us, and what it becomes for Junker. Slowly, slowly, as Yumemi's enthusiasm and passion warm Junker, the ice encasing his heart defrosts. Never fully. But enough that she can reach forward and feel his pulse.

Hoshino Yumemi's name written in Japanese officially is ほしのゆめみ. But it could also, with the right kanji, be written like this: 星の夢見. “Dream of a Planet” is how that translates. “Wish Upon a Star” is how the official English translation interprets its meaning. However one chooses to transcribe her name, its message still carries.

Why don't you come to the planetarium?

Planetarian ~the reverie of a little planet~ is a very short package, but there's so, so much to it. I was pacing in circles trying to figure out how to talk about its themes, how in-depth I should go, and how to connect it all, and I simply lack the writing skills to adequately lay it all out in the manner this story deserves. Calling what I settled on a compromise sounds rather brusque, so instead, let's go with formal invitation, from me to you, to immerse yourself in this scarred world and discover the beauty in it.

Planetarium does have a prequel, Snow Globe, but I opted against playing it for two reasons. Firstly, because I don't think my poor heart could handle it. Secondly, for the same reason I refuse to play any of the sequels of AI: The Sominium Files: because it tells a fantastic story that closes on a perfect note that doesn't warrant a continuation before or after the story's conclusion.

Ever since reading this visual novel, I've had a certain refrain rooted in my head. It comes from Yumemi. I handed you my invitation, and this is Yumemi's, welcoming you to the planetarium so that you may sit in awe at the countless, countless stars encompassing our tiny, blue marble. It bids us, like a poem, to sit before something so small, so insignificant, so distant, and admire it as something so grand, so outstanding, so dear.

Why don't you come to the planetarium?

The beautiful twinkling of eternity that will never fade, no matter what.

All the stars in the sky are waiting for you.

Why don't you come to the planetarium?

Just writing about the video games that tickle my fancy when the fancy strikes.

posted by Ross Locksley on 11 Feb 2026

posted by Jared T. Hooper on 06 Feb 2026

posted by Eoghan O'Connell on 04 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Locksley on 03 Feb 2026

posted by Jared T. Hooper on 21 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Locksley on 16 Dec 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 10 Dec 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 01 Dec 2025