Written by Majkol Robuschi on 29 May 2025

Distributor Netflix • Certificate NA • Price NA

Recently made available to international audiences via Netflix, The Rose of Versailles is a feature-length animated film that faithfully revisits the key events of Riyoko Ikeda’s groundbreaking manga by the same title. A true cult classic and a transformative work within the shoujo genre, the comic series—known affectionately in Japan as Berubara—is widely regarded as one of the most culturally impactful narratives to emerge from Japan in the early ‘70s. Its enduring legacy stems largely from Ikeda’s bold decision to recount the life of Austrian-born Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, framing her biography within a delicate balance of historical reconstruction and dramatic fiction that resonated deeply with the sensibilities of young female readers of the time.

Among the fictional characters who share the spotlight with Marie Antoinette, none has left a more lasting impression than Oscar François de Jarjayes—a strikingly androgynous woman raised as a man by her father, a general in the royal military. These two lead figures anchor a web of themes, including a complex romantic triangle among young nobles, reflections on femininity. Ultimately, they become entangled in a doomed love story strained by class boundaries. These core themes are explored through intertwining storylines that also include the captivating André Grandier—Oscar’s childhood friend and loyal servant—and Hans Axel von Fersen, the Swedish count infatuated with the French queen.

Yuri innuendos, coupled with the tragic allure of a romantic drama set against the magnificent backdrop of the Palace of Versailles, contributed to the manga's adaptation into several other media. First, it was transformed into a stage play by the Takarazuka Revue, becoming a cornerstone of the female-only troupe’s repertoire and still performed to this day. It was also adapted into a live-action film in 1979, directed by French New Wave filmmaker Jacques Demy and featuring an entirely Western cast.

Outside of Japan Berubara is primarily known through its 41-episode anime adaptation, broadcast in Japan between 1979 and 1980. Produced by Tokyo Movie Shinsha and initially directed by Tadao Nagayama—later replaced by Osamu Dezaki due to Nagayama’s health issues—this adaptation arrived nearly a decade after the manga’s conclusion.The anime stood out for its strong directorial identity and striking visuals, particularly the refined character designs by Michi Himeno and Shingo Araki. Their take on the story’s tragic atmosphere was immediately apparent in the dramatic opening sequence, where Oscar’s silhouette, draped in roses, stands out against a tangle of shadowy rose thorns. However, despite being beloved by international audiences for its more overly dramatic tone, this adaptation failed to satisfy its most critical audience: Japanese fans. Riyoko Ikeda herself has expressed disappointment over time with the way the anime altered her most recognized and celebrated work.

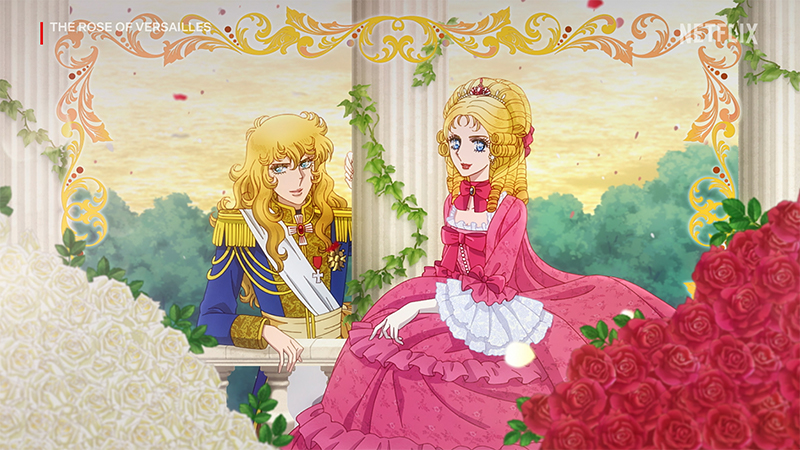

Back to the present: The Rose of Versailles returns after more than 40 years as a two-hour animated feature by Studio MAPPA, produced in collaboration with Riyoko Ikeda Production. More than a straightforward adaptation, the film serves primarily as a celebratory homage to the original manga: a visually rich, female-led production aiming to reintroduce the story to contemporary audiences. It marks the feature-length directorial debut of Ai Yoshimura, with the screenplay penned by seasoned writer Tomoko Konparu, who faced the challenge of condensing an epic saga into 113 minutes. Character design was handled by veteran artist Mariko Oka, while the score—departing from Koji Makaino’s emotional and raw compositions in the earlier adaptation—was crafted by Hiroyuki Sawano of electronic influence. Rather than retelling the full narrative, this version offers a curated selection of highlights from the manga, functioning more as a commemorative piece than a comprehensive adaptation. This choice inevitably results in narrative and stylistic compromises, as the film attempts to convey the dualities of 18th-century France: courtly opulence and street-level poverty.

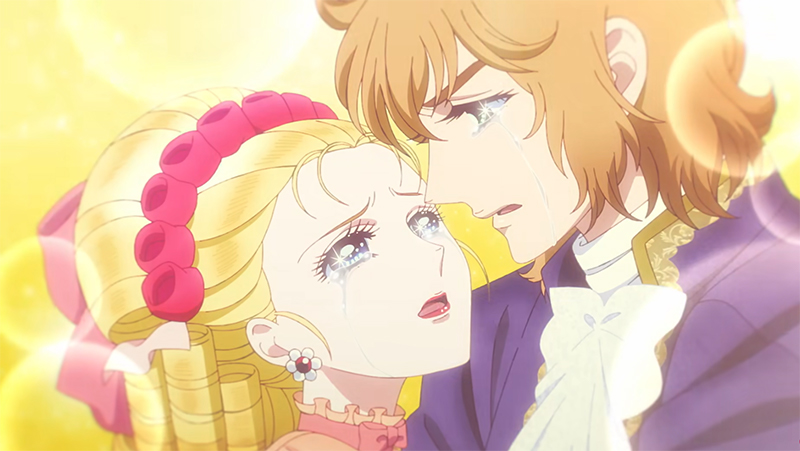

Consequently, while the central threads involving Oscar, André, Marie Antoinette, and Fersen are explored, they remain selectively developed as their arcs are presented more as visual impressions than as fully fleshed-out developments—presuming a degree of familiarity with the source material. This assumption works well in Japan, where the manga is deeply woven into pop culture and frequently cited in works by later creators (including Kunihiko Ikuhara’s Revolutionary Girl Utena and numerous nods in series like Ranma ½, Pokémon, or Hamtaro). However, it may hinder accessibility for international audiences unfamiliar with the original anime or the source material.

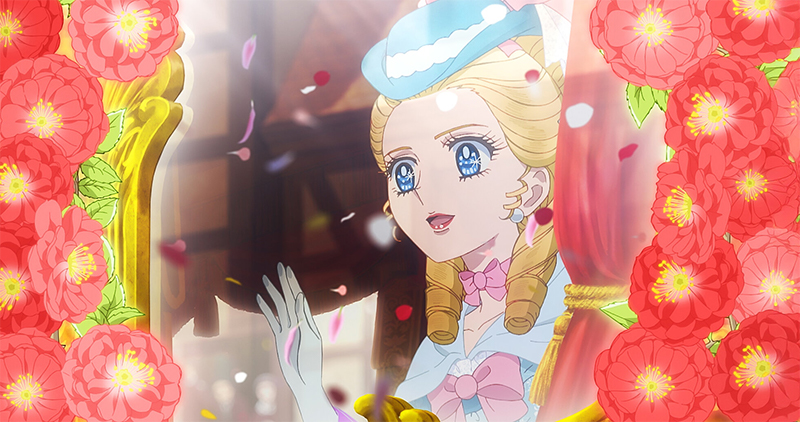

The film premiered theatrically in Japan in early 2025, faithfully echoing Ikeda’s original art style and blending key narrative sequences with diegetic musical numbers performed by prominent voice actors. Aya Hirano (Haruhi in The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya) and Kazuki Kato (Kikyo in Reborn!) deliver compelling portrayals of Marie Antoinette and Fersen. But it is Miyuki Sawashiro (Kurapika in Hunter x Hunter) who stands out as Oscar, capturing her inner turmoil and strength. Toshiyuki Toyonaga (Mikado in Durarara!!) plays a somewhat underdeveloped André, mainly due to limited screen time, while notable cameos include Akio Otsuka (Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid) and Miyu Irino (Sora in Kingdom Hearts), the latter performing one of the film’s few songs not centered on the main quartet.

The pacing is brisk, shifting between opulent ballroom scenes and stylized musical interludes that convey characters’ emotions in music video-like sequences. These segments, while visually striking, often truncate plot points in service of a swift progression toward the climactic finale. There, the film slows to provide a more traditional and poignant depiction of Oscar and André’s closing arc. The animation remains consistently polished, supported by richly detailed backgrounds and vivid color palettes that capture historical ambiance. Outside the musical interludes, the direction is largely conventional, aiming to faithfully replicate iconic manga panels.

The musical numbers serve as homage to the Takarazuka Revue’s influence, yet Sawano’s J-pop compositions sometimes clash with the film’s European-inspired setting. Only one track—"May Our Souls Bloom in Love,” which accompanies Marie Antoinette’s arrival in Paris—truly succeeds in marrying emotional weight with visual grandeur. While unfair to directly compare adaptations from different eras, it’s difficult not to recall the operatic "Bara wa Utsukushiku Chiru" from the 1979 anime. Still, it’s evident that the production team deliberately distanced this project from the historical adaptation in both tone and structure. The goal seems to be to realign the story more closely with Ikeda’s manga, offering something more stylistically and thematically consistent with her vision—an approach reflected by her active role in overseeing this new adaptation as a creative consultant.

Majkol (aka Zaru) is an Italian queer writer (he/him – they/them) who has been immersed in the world of video game journalism for almost two decades. With a deep-seated love for anime and manga shaping his tastes and passion, he brings a blend of critical insight and heartfelt enthusiasm to his work, celebrating stories that challenge norms and embrace diversity. Find him on his blog, Also sprach zaru_thustra.

by Ross Locksley on 06 Oct 2025

by Ross Locksley on 29 Sep 2025

by Ross Locksley on 23 Sep 2025

by Ross Locksley on 22 Sep 2025

by Xena Frailing on 01 Sep 2025

by Ross Locksley on 01 Sep 2025

by Ross Locksley on 25 Aug 2025

by Ross Locksley on 01 Jul 2025