Written by Richard Durrance on 14 Jun 2022

Few films feel almost unclassifiable or uncategorisable (is that a word? - Ed), A Snake of June has always felt to me one of the rare few that genuinely fits the criteria. Ostensibly Lynchian, Shinya Tsukamoto’s film fits more snugly with an outing like Guy Maddin’s Careful in being utterly unique and most definitely a work of art. It shares aspects with the work of Pedro Almodovar, in being able to take what seems an appallingly tasteless concept and makes of it something quite profoundly different.

Released in 2002, A Snake of June has hit its 20th anniversary, and for me this was a gleeful excuse to re-watch the film. I’m old enough to not remember when I first saw it, as I cannot honestly remember if the film was ever released in cinemas. Was the DVD my first exposure? His follow-up, Vital, I remember watching in the now obliterated Cineworld in the Trocadero (also obliterated) with about five other people including my mate I dragged along to watch it with me. But A Snake of June? I’m not sure if I had the luck to watch with it towering over me, but I remember it’s impact on me very, very vividly.

To try and describe the plot of A Snake of June is difficult and problematic. If you want, watch Mark Kermode’s BFI Player intro here. But should you? Should I even tell you anything of the story? Yes, I’ll probably have to give some things away but it comes back to the essential point that in making A Snake of June, and in the lead performances, most noticeably the lead role of Rinko, played by gravure model and actress, Asuka Kurosawa, Shinya Tsukamoto created an artwork that so totally transcends a mere description of the story and circumstances in which the characters find themselves. Also, like Maddin’s Careful, it’s one that strays into perverse relationships, which for some might seem a step beyond what they feel comfortable watching.

In both instances the loss is theirs.

Those who know Tsukamoto’s work will recognise how his films are stylish and often kinetic, but one aspect that has for me always set Tsukamoto’s skill apart is his ability to adjust the tone at a moment's notice to something slower, more precise and more overtly poetic, yet without it ever being jarring in tone, so that his films exist as a consistent, coherent whole. A Snake of June feels like a more consistently poetic and precise film, and perhaps a more personal work.

Some aspects are immediately apparent but also extremely important to the feel of the film.

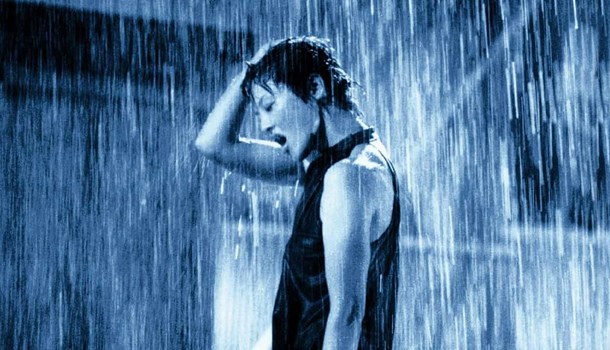

The story concerns Rinko, a counsellor on a hospital support line and a man dying of stomach cancer named Iguchi, who in Rinko finds a new reason to live. His actions seek to disrupt Rinko's barely functional relationship with her husband, Shigehiko, and within all this two things strike you: the film’s black and white blue tinted beauty and the claustrophobia of the 4:3 ratio - no widescreen here.

The depth of intensity and intimacy these factors create for Tsukomaoto are remarkable, and is often heightened by how characters are set into close spaces: the couples' narrow kitchen; Shigehiko crammed into the edge of his office, out of sight as he makes sweaty phone calls; Rinko’s cubicle, though often as not Tsukamoto uses extreme close up on her face. It's film as aesthetic, the image of a snail on a leaf appears and reappears through a film suffused with rain and moisture: it’s forever raining, sometimes dripping through open vents or cascading off umbrellas or battering skylights. There’s Rinko’s face coated with moisture as she lays in the bath. We’re in nether Japan, a nameless city, a space that exists for our characters and their dysfunctional relationships. A close, distant, curious, perverse and judgemental space.

As the film unfolds, Tsukamoto’s Iguchi begins to manipulate Rinko and Shigehiko into exploring, recognising and accepting their desires, personalities and feelings. Social mores are investigated and yet this all seems such a poor definition of the film. Though broken down into roughly three parts, Kurosawa’s Rinko is the dead centre of the film and there is a fearlessness about her performance that transcends what could be a trashy role in a trashy motion picture, if all involved were anything other than the skilled artists they are.

Instead, as Rinko is sent around the city, in scenes that in a lesser film would have her rights, feelings and body violated, you recognise that what is going on is something far, far subtler and in some ways more disturbing, because as Iguchi pushes Rinko towards lines she feels she can only cross when alone, we find ourselves understanding and, to put it in the terms of genre film, rooting for both characters. We want Rinko to be pushed by Iguchi but not out of any prurient exploitation but because Tsukamoto posits Rinko’s journey as one of emancipation, from many of the shackles that bind her life. Yet Rinko always very much exists as a woman, just as Iguchi does as the dying man with renewed purpose, just as Shigehiko is no mere cypher distant husband. Key to this is how the film could easily have dropped into generic power games, but it never falls into such shallow conceits, even if at times characters are very overtly manipulated. Iguchi is very, very honest. So we recognise even if his methods are deeply questionable and very disturbing his motives are anything other than. Considering the erotic content of the film, this makes A Snake of June seem easier to misjudge.

If you look online some people call it an “erotic thriller”, and there are aspects that ring true to this, but the observation so utterly misses the point. A Snake of June strips away social aspects so very close to the bone. True, so does a film like Basic Instinct (and I’m old enough to remember the furore when that came out), which has a policeman who is an addict, a shooter and generally unlikeable man and a woman who is a murderer but very, very honest about her sexual feelings (and if anything is the most sympathetic character because she is totally without bullshit). But A Snake of June never fits that Basic Instinct bill for a moment, and takes the audience into a territory that is purely Tsukamoto. In some ways I equate it to his most recent film, Killing, which is more poetic yet disturbing, even if less obviously so than A Snake of June, yet it also questions social norms, even if more in the aspect of the samurai’s code. Either way, any aspect of hero or villain, abuser or abused become so utterly intertwined that as a viewer you cannot make them out, if ever they even exist at all. It’s this sophistication that makes the film, and reminds you of Pedro Almodovar: you just have to think of Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down, and how the hell is that a romantic comedy when you should be vomiting up your lungs in disgust rather than enjoying the absurdist romanticism.

For me perhaps the great beauty of A Snake of June is that this is a film I feel I just cannot fully quantify, clarify or even on some levels fully understand. Writing about films it’s very easy to try and suggest you get it, understand it, can explain it all away, and forget that often one of the greatest things about a film is that you can't always do this, that you forget and rediscover films that left you haunted, where rather than deconstructing the work, you feel it on a visceral level,. And does A Snake of June do this?

Oh yes it does.

Let me tell you something. I had just finished watching a mid-fifties British thriller, The Man Who Never Was (which, coincidentally tells the same story as the recent Operation Mincemeat), then needed something else. I started watching one of the two Pete Walker films that had turned up: Die Screaming Marianne (charming title I’m sure, but is it better than the other: House of Whipcord? I don’t know but actually the latter at least I’ve seen and like Tsukamoto’s work is not what it seems or in that case sounds like... anyway). I got five minutes in and was twitchy. So instead, meaning already to watch it for its birthday, I reached for A Snake of June, and from the first moments of the film it cast its same spell. The images, the sounds, the performances, the music coalesced into a gorgeous cinematic experience we so very rarely, if ever, have the incredible good fortune to watch, in part because of the sheer bravery of the film making.

Yes, I may have re-watched Tetsuo II: Body Hammer more times, but I have no single doubt in my mind in saying that I feel A Snake of June is Shinya Tsukamoto’s finest film. Its sophisticated, erotically charged journey, its move into perverse scenes out of a Lynchian nightmare and final cathartic bliss is executed with unerring skill and all in a film only just over 75 minutes long.

If I was stuck on a desert island, I would take A Snake of June with me, along with those few films that matter. Or, to paraphrase the great critic Philip French talking about Singing in the Rain, I’d run into a burning building to rescue the only copy of it.

A Snake of June is available in restored blu-ray from Third Window Films, and can be streamed on the BFI Player and Terracotta VOD. So don’t take my word for it, watch it, and fall under the spell of A Snake of June.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 17 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 13 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 02 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 31 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 30 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 27 Jan 2026